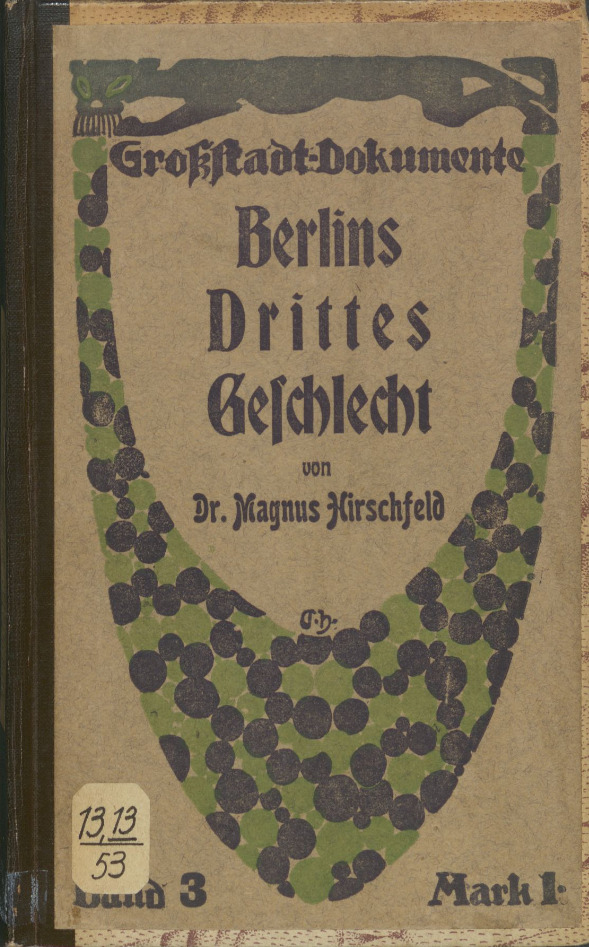

Berlin’s Third Gender (Berlins drittes Geschlecht) by Dr Magnus Hirschfeld is a description of queer lives in Berlin around 1900 (published 1905). Even though it’s naturally sad in some ways, it’s also encouraging: Berlin was comparatively liberal at the time, and I enjoyed the descriptions of queer groups, events, relationships, and creative side-stepping of general conventions. The descriptions are very vivid and obviously well-researched, and contain lots of amusing facts about everyday life in different social circles.

Hirschfeld is not without his problems (he never really believed that homosexuality was quite as good as heterosexuality), but in this book, it barely shows. In reading queer history, you probably won’t find less depressing books than this one.

Gems in this book include:

- You can’t understand Berlin without understanding gay people.

- “I know more than one woman who appears completely like a man when at home.” (Note how he respects the chosen gender!)

- Gay people are everywhere, and are the driving force behind a number of restaurants, cafes, small theatres, gymnastics clubs.

- Descriptions of compersion that a gay person feels towards the heterosexual partner of their crush: “I can’t even say that I was jealous. More like the opposite: A part of my love to K. was transferred to his girlfriend for making him so happy.”

- “Stable long-term relationships of homosexual men or women are very common in Berlin.”, arguing against assumptions of “loose” (implied: amoral) relationships.

- Both very feminine and very masculine gay men are represented, and of course a lot of people in between those extremes. Among the more feminine gay men, so many were dressmakers that it was worth pointing out in the book.

- Family life: Hirschfeld notes that many parents are okay with their kids being gay, but that others lose their family completely. Some wealthy gay people invite the others for very high-class fancy Christmas dinners to make sure they aren’t alone and sad while their families meet without them.

- Parties. Balls. Celebrations. Small groups of friends or acquaintances. Large groups that meet again and again – not always within their social class, but sometimes. He reports a regular group of gay princes, counts and barons, and a monthly meeting of Lesbian Jews in a particular cafe, where they like to eat cake and play chess. “Homosexuals from the countryside often cry when they enter a place like that for the first time.”

- Suicide was not uncommon, both due to unhappiness, but also related problems: Blackmail of homosexuals was rampant, and if people lost their jobs for their sexual orientation, they often killed themselves rather than telling their family the truth. Notably, the blackmail was not condoned by the police, who were surprisingly lax and cooperative, and never stationed any agents provocateur, even though it would have been easy.

Interestingly enough, the book was published when the term “homosexual” was in use already, but not firmly established in Germany yet, and the book uses the term “Uranian” instead (heh.), which I hadn’t heard before. The author argues that “homosexual” will make people think that it’s all about sex (and I can imagine that with 1900s sensibilities, he wasn’t wrong.). He he stresses that queer groups are a socially oriented, and that the sex itself is no more (or less) important than in heterosexual groups.